The first principle in the Agile Manifesto is “Individuals and Interactions, over processes and tools”. A recent development task illustrated that point starkly – skill trumps process.

Time’s a wastin ….

I was working through a weekend, exhaustively specifying the UI (mockups, WORD docs, UML State diagrams) for a recent user story, when it occurred to me that we were wasting our time.

Here is more or less the user story I was working on.

As a documentation processor, I must be able to review all of the documents in a mailbag. Upon review, I must be able to accept, or reject each of these documents.

In the time that it was taking to describe the UI to its last gory detail, I could create a working prototype of the UI, which would be close to 80% of what the user needs. The business folks could take the prototype for a spin, and give me feedback, which could quickly iron out the remaining 20% of the work.

See, we are building this for processors in an insurance company. They are not looking for sophisticated, space age UI. They just need something that is easy to understand, learn, and allows them to do the work efficiently.

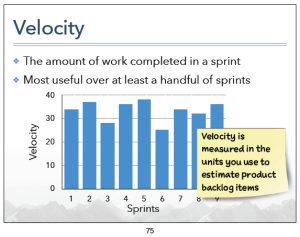

Between the business analyst and me, we could have the UI squared away in a couple of weeks – a single sprint. Add a tester if you must.

I will test every damn line of code I write anyway, before this leaves my hands. The tester is only a second line of defense. Even without that tester, I can get this very close to done.

So why am I specifying the UI when I can just build the thing myself? I am having to do this because, collectively, the primary resources that are assigned to this task cannot or will not, produce an effective UI on their own. That amazes me. I am shaking my head as I write this. If you have several years of experience with this problem domain, with these business analysts, with these end users, and with the same UI technology, you should be able to take the user story, fill in all the missing details, and end up at the UI.

Again, here is the user story, for reference.

As a documentation processor, I must be able to review all of the documents in a mailbag. Upon review, I must be able to accept, or reject each of these documents.

Let’s think through this.

Analysis

- Users have to review all the documents in the mail bag.

- This means you have to list the documents to the user

- So how do you present a list of documents.

- A table, where each column is some attribute of the document, and each row is a document.

- How do you make it easy for a user to study a large list of data that is in a table?

- Allow filtering and sorting by various attributes.

- Break up the list into several pages, and allow the user to page

- Or simply allow the user to scroll up and down the large list.

- How do you help the user make changes to large amounts of data safely, and correctly?

- You must ask the user to confirm a large change. Give her a chance to back out.

- You must provide the user a way to undo a change. Mistakes will happen.

- What attributes (columns) of the documents must be included in the list

- Leave out the attributes of the documents that are implementation-centric, which users have no need to know.

- Pick the attributes that are business information. Make a guess on which of these the user might be interested in. Changing this list after review should not be hard.

Can’t the developer do this?

Analysis

If you have been developing UI for any time at all, you should be able to do the analysis I just did, and arrive at a similar, if not the same place.

Business Info

You have been working in this domain for several years. That means you must already have all the business information you need.

You must know the business-centric attributes that characterize the mailbag and documents. These become the columns of your listing, and suggest what the user can sort and filter on.

Language and jargon that end-users will recognize must also be familiar to you by now. This is where static labels, feedback messages and such will come from.

Implementation

You have been working with your UI framework for several years. So you should know how to implement the various UI features mentioned above – a table of data, sorting, filtering, paging, scrolling.

But none of this happened

But none of this happened, and a UI designer had to be brought in to spell everything out. Why?

The Developer

Though they were well-versed with the UI framework, the developers have little knowledge of, or interest in, what makes an effective UI.

They are happy to be told what to build. They want to be told what to build. When left to their own initiative earlier, they produced a UI that so defied common sense and business reality, that the end-users’ job turned into a labor-intensive, error-prone, hell.

The Tester

If the testers know the lingua franca of the business (English, in this case), if the testers know the business, and if they know the end-users, the testers can judge if the UI satisfies the business need, simply by relying on the 2 sentence user story.

Unfortunately, testers’ familiarity with the business is uneven. They are simply kids that compare a spec to delivered software. If the spec is incomplete, or incorrect, these testers are thrown off course.

Further, more often than not, the testing leadership subscribes to the view that testers must only work off an exhaustively detailed spec. Applying their own knowledge of the business, their own analytical and communication skills, is considered risky. The focus on learning the business themselves is weak.

Manager

Well, managers have all the power, which makes them responsible for everything, doesn’t it?

Who are they hiring?

The UI developer does not exhibit knowledge of effective UI design. So how did we end up hiring him?

Say the manager that is evaluating the developer does not know anything about UI design himself. So the manager cannot determine the developer’s competence in the matter. That is reasonable and common. A manager is constantly confronted with problems in which he does not have direct expertise. Yet, she must hire people that will be responsible for solving that problem. In that situation, a manager has to be able to recognize competence (and conversely, incompetence) as a characteristic separate from concretely observable skill. Competence has an aura, a body language, a speech pattern, a look in the eye, as does incompetence. You have to be able to smell the bullshit before you see it.

When managers neither have concrete expertise, nor do they have a nose for fakery, we end up with these half-baked developers that require to be spoon fed.

Bad drivers

Many resources are able to learn and do more if we create the right environment. This is usually some combination of large grained carrot and stick, coupled with the pushing of buttons that we can only learn by getting to know the resource personally.

Effective UI design for the corporate world, is a skill that can be learned by just about anyone in a few weeks, or over the course of a few UI development tasks. If a developer has worked on UI development for going on three years, and still does not have a coherent, useful view of the matter, the leadership has been asleep at the wheel.

The same argument applies to the testers. The management enabled them to be unthinking, ‘garbage in garbage out’ type grunts.

Skill trumps process

What a business analyst and a skilled engineer can take care, is now distributed over a whole platoon – The business analyst, the UI designer, the developer, the tester, tech and test leads to oversee the grunts, managers to oversee all of this.

Where the work could simply be a conversation between two people, now is a multi-step workflow involving many more people than that. Two people getting a task done is just work. Eight people, each with their own inputs, and deliverables, working on narrow parts of the whole, and that with their vision constrained by blinders, is a process.

What does the process buy us? Nothing that I can see. I see overhead. An 8 to 10 person team requires more management and book-keeping than a 2 person team. I see a machine with more moving parts, which exponentially increases the complexity, the amount of co-ordination required, and the number of ways the process can fail.

One or two committed, skilled engineers can replace the whole process. Why not learn to identify, hire and hold on to such resources? Why the fixation on process? Do you want get work done? Or do you want to run a process?